Lede

If you came for romance, Brontë hands you obsession, then asks you to call it truth.

Hermit Off Script

Wuthering Heights does not flirt. It grips. The love at its centre is not a warm room with a kettle and a plan. It is weather. It is the kind of attachment that feels older than choice and more violent than desire. Brontë writes passion as a force that drags people across class lines, across households, across years, and still does not learn manners. If you want “real love” in the clean, human sense – tenderness, steadiness, sacrifice without possession – this book is not a manual. It is a warning label. The desire is there, yes, but the deeper thing is the fixation: the refusal to let the other person be separate. And Brontë does something brave: she does not soften it to make you comfortable. She lets it rot, spread, and shape the next generation. That is why it lasts. The structure matters. You do not get a simple, flattering viewpoint. You get a story told through layers, with witnesses, retellings, bias, and memory. It feels like hearing a legend in a village pub, except the legend is about two households being emotionally napalmed for decades. The moors are not just scenery either: they are the book’s nervous system. Wildness is not a vibe here; it is the moral climate. So yes, there is love. But it is love as storm, not Valentine. Read it for the poetry of the bleak, the psychology of possession, and the way Brontë makes nature and character feel like the same animal.

Book review: Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

This is not a comfort read. It is a storm trapped in a book, and it still rattles the windows nearly two centuries on. Published in 1847 as Emily Bronte’s only novel, it blends romance, realism, and Gothic unease, and it was notorious from the start for seeming “immoral” to early reviewers.

If you come looking for polite devotion, you will feel cheated. Bronte’s core feeling is wilder than that: love as identity, love as a shared substance, love as something that does not ask permission from manners, religion, or social class. Catherine’s most famous confession is not “I desire him” but something more unsettling and more metaphysical: “Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same.” That line is the novel’s heartbeat. It is passion described as sameness, not sweetness. It is a bond so absolute it sounds holy, and so absolute it becomes dangerous.

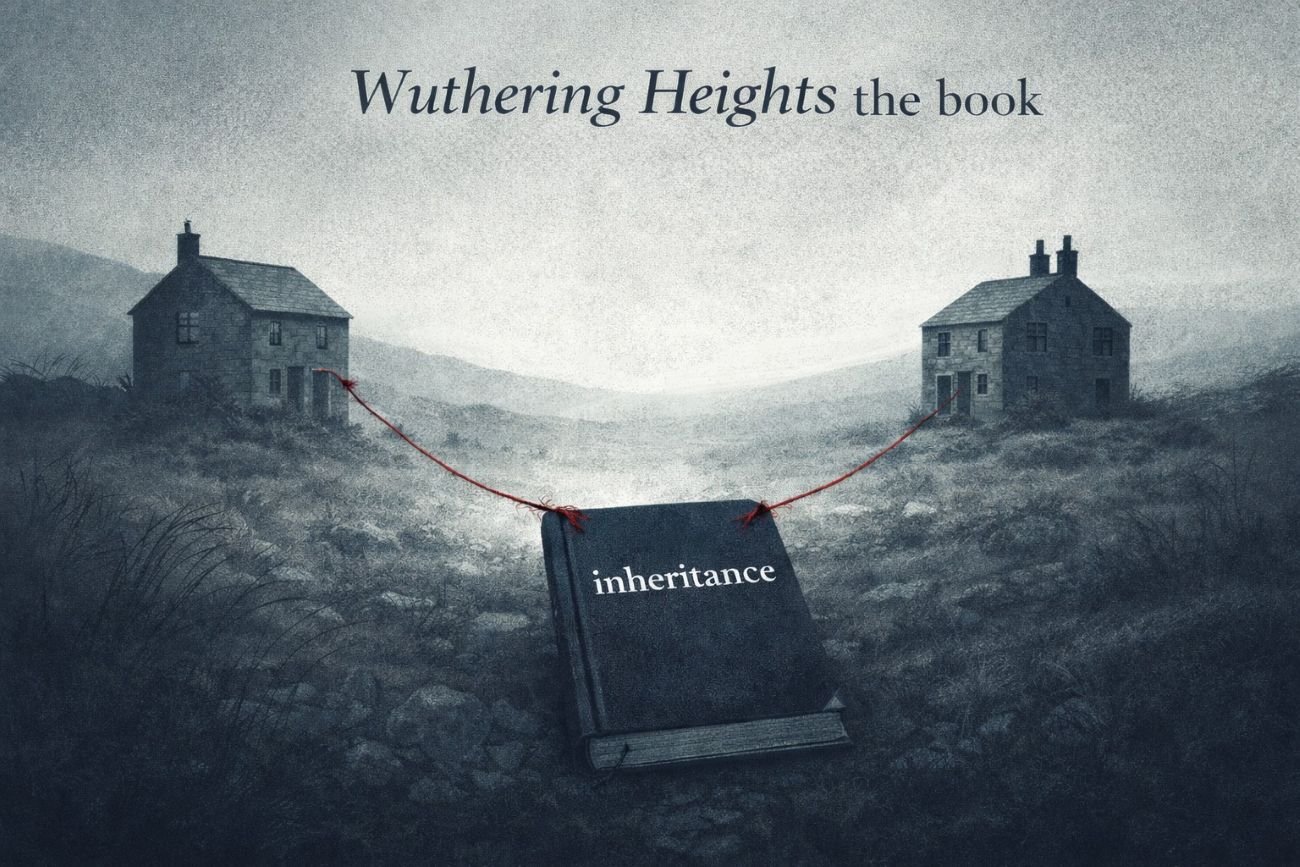

Bronte is ruthless about what that kind of passion does when it is boxed in by pride, property, and hierarchy. The book keeps showing how love can turn into possession, and how the wound of being “less than” in a class-bound world can rot into revenge. Britannica is blunt about the novel’s centre of gravity: obsessive love, brooding nature, and ghost-story elements that push it firmly into Gothic territory rather than tidy romance. The moors are not wallpaper. They are a force, like weather with opinions, and the people in it start behaving like weather too.

One reason the feeling lands so hard is the way Bronte tells it. The story comes through layered voices and recollections, which the British Library notes as multiple narrative viewpoints. That distance matters. You do not get a clean, cinematic “here is the love story” line. You get a human mess: memory, bias, gossip, confession, cruelty, and tenderness arriving in the same breath. It reads like overhearing a household trying, and failing, to explain what happened after the fact.

Heathcliff and Catherine are often sold as “romantic”, but Bronte does not romanticise what they do to other people. Their connection is real in the way a fire is real: it gives heat, it gives light, and it also burns the house down. The novel constantly contrasts their feral, consuming attachment with more socially acceptable forms of love that offer safety and comfort. Even summary guides tend to agree on that contrast: the “civilised” option is calmer, but it cannot compete with the deeper, more violent pull Bronte builds between the two central characters. What makes Bronte feel honest is that she never pretends the fire is harmless.

And that is the key difference between passion and mere desire in this book. Desire can be loud and simple. Bronte’s passion is complicated, often ugly, and frequently spiritual in its language, even when the characters behave like animals backed into corners. When Catherine compares the difference between Heathcliff and Edgar to “moonbeam from lightning” and “frost from fire”, it is not erotic sales copy. It is a writer trying to describe incompatible forms of being.

Style-wise, Bronte writes with “rugged power”, as the British Library puts it, and she is not interested in smoothing the edges for your comfort. The book is full of harshness, but it is not empty bleakness. There are quieter human loves in the margins, small acts of care and endurance that show what love looks like when it is not trying to conquer. Those moments matter because they stop the novel becoming a single-note hymn to obsession. They also make the central tragedy sharper: you can see other paths, and you can see how pride and fixation keep choosing against them.

My verdict: if you want “love and passion” as Bronte meant it, read this as a tragedy of two people who confuse unity with entitlement, and intensity with destiny. The feeling is immense, but it is not a model to copy. It is a warning written in thunder.

If you want the glossy, modern, desire-forward remix instead, watch the film and let it do its loud, expensive thing.

What does not make sense

- People keep calling it a “love story” as if love is automatically healthy.

- It gets marketed as romance when it behaves like Gothic tragedy.

- Readers expect one narrator, but Bronte builds a relay race of voices, then lets ambiguity do the work.

Sense check / The numbers

- Published in 1847, it is Emily Bronte’s only novel. [British Library]

- Bronte published under the pseudonym Ellis Bell, partly to dodge prejudice against female authors. [Britannica]

- The novel centres on a “passionate and destructive” relationship and leans into Gothic elements like brooding nature and ghosts. [Britannica]

- Early reviewers were split, with some calling it immoral and others praising its “rugged power”. [British Library]

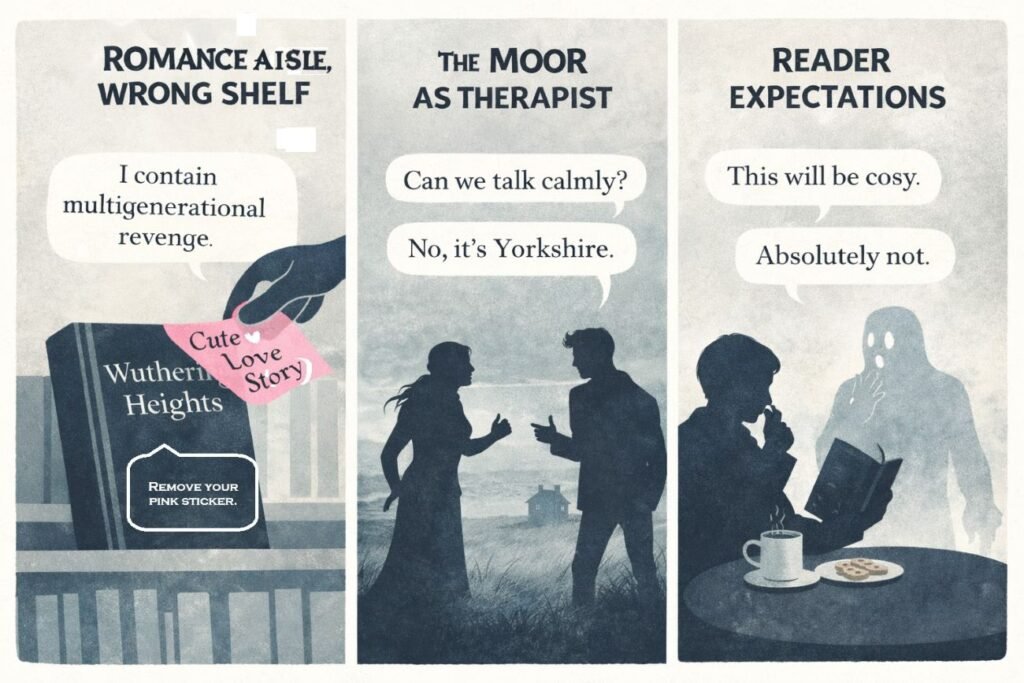

The sketch

Scene 1: “Romance aisle, wrong shelf”

Panel: A bookshop sticker reads “Cute Love Story”. The book itself looks offended.

Dialogue: “I contain multigenerational revenge.”

Dialogue: “Remove your pink sticker.”

Scene 2: “The moor as therapist”

Panel: Two characters argue. The wind refuses to mediate.

Dialogue: “Can we talk calmly?”

Dialogue: “No, it’s Yorkshire.”

Scene 3: “Reader expectations”

Panel: A reader opens the book with tea and biscuits. A ghost coughs politely.

Dialogue: “This will be cosy.”

Dialogue: “Absolutely not.”

What to watch, not the show

- How class and property shape intimacy.

- How trauma breeds repetition across generations.

- How narration and gossip distort “truth”.

- How nature can act like character, not backdrop.

- How obsession gets dressed up as destiny.

The Hermit take

This is not a romance. It is a masterpiece about what romance can turn into.

If you want comfort, read something else. If you want honesty, stay.

Keep or toss

Keep

Keep it for its ferocity and poetry.

Toss only the fantasy that it will behave like a healthy love story.

Sources

- The British Library overview: https://www.britishlibrary.cn/en/works/emily-bronte-s-wuthering-heights/

- Britannica overview: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Wuthering-Heights

- Wuthering Heights – Emily Brontë, Pauline Nestor (Editor/Introduction), Lucasta Miller (Preface): https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/32929156-wuthering-heights

Leave a Reply to Wuthering Heights (2026): Bronte, but make it thirstier – The Modern Hermit Cancel reply